Crater Lake, Oregon, was a place I wanted to see since I first read about it, in a book when I was a kid. On top of that, as an amateur geologist I'm interested in volcanoes and volcanic geology. Well, if you want to see volcanoes and young volcanic landscapes in the US, you head for the Cascades Range in the Pacific Northwest. When I found that the World Science Fiction Convention for 2002 was being held in San Jose, CA, and that San Jose isn't all that far from Lassen Peak, the south end of the Cascades, the conclusion seemed obvious.

So after spending Labor Day weekend at Worldcon, I used the next five days to do a driving tour of the southern Cascades Range, from San Jose to Mount St. Helens. Along the way I stopped at Lassen Peak National Park, Mount Shasta, Lava Beds National Monument, Crater Lake, and Mount St Helens National Volcano Monument. On this first day, I drove north from San Jose to Red Bluff CA, then spent the afternoon in Lassen National Park, home to Lassen Peak and a swarm of other volcanic landforms.

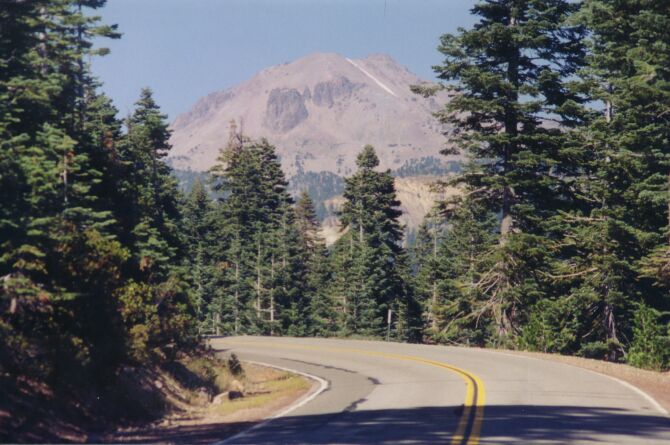

Lassen Peak seen through the trees from a few miles away

- In California:

- Lassen Peak

- Mt Shasta

- In Oregon:

- Mt McLoughlin

- Mt Thielsen

- Crater Lake/Mt Mazama

- Newberry Caldera

- Three Sisters

- Three-Fingered Jack

- Mt Jefferson

- Mt Hood

- In Washington:

- Mt Adams

- Mt St. Helens

- Mt Rainier

- Glacier Peak

- Mt Baker

- In British Columbia:

- Mt Garibaldi

- Meager Mountain

Information on all of them can be found at the USGS website.

Lassen Peak and its namesake park are located near the southern end of the Cascades Range, a long chain of volcanoes and volcanic landforms that extends north into British Columbia. Lassen National Park includes Lassen Peak and several other mountains, all volcanic in origin, and huge numbers of smaller volcanic features such as geysers, steam vents, mudpots, fumaroles, etc. To me it was interesting for two major reasons: first, it made a convenient starting point for my volcano tour; second, it last erupted in 1921, which makes it the second-most-recently-active volcano in the Lower 48 states.

Lassen Peak is the southernmost of the major volcanoes in the Cascades Range. The Cascades are a consequence of plate subduction: just off the Oregon and Washington coasts, the small Juan de Fuca Plate is being forced down into the Earth's interior by the North American Plate. As the Juan de Fuca Plate sinks and slowly melts, pockets of magma find their way up to the surface and produce the Cascades volcanism. Cascades volcanic activity runs the full gamut from quiet steam venting up to major mountain-building lava flows, mudflows, and gigantic nuée ardente ("burning cloud") eruptions. My trip wound up taking me over a variety of volcanic landforms, though unfortunately (or perhaps very fortunately) the only volcanic activity I actually saw was steam and gas venting at a single location here in Lassen Park.

Lassen Peak taught geologists a lot about volcanoes. In the early 20th century volcanology was a young science, and geologists believed that no evidence of recent lava flows and no mountain-top crater meant a volcano was probably extinct. Lassen Peak proved how wrong that belief was. The mountain came to life in 1914 for an eruptive cycle that lasted a total of seven years, fading off into occasional steam eruptions that finally ended in 1921. The most powerful eruption was an ash/lava/gas eruption on May 22, 1915. Within a couple of years it was quiet again, but it's no more dead now than it was prior to 1914. The history that geologists have pieced together for Lassen, its companions, and the older volcanoes beneath indicates strongly that the volcanism here is not over, that there will be more eruptions in the future. Even today, when the major volcanoes in the park are all quiet, it's still one of very few places that an ordinary tourist can go to safely (more or less) see active volcanic activity. Right now the volcanic activity in the park is minor, only gas vents and hot water springs, but that's still more than you can find in most places.

I stumbled across this while updating this page in 2018: a film of one of Lassen Peak's larger eruptions. It may even be the big eruption of May 22nd; there's a striking similarity between this film and films and photos of the big lateral-blast eruption from Mount St Helens, in May 1980. This film was taken by Justin J. Hammer of Red Bluff, CA. It was lost for a long time, but found, restored, and posted online by the Shasta Historical Society.

Lassen is unusual for a Cascades volcano. Where most Cascades peaks are stratovolcanoes made of lava flows mixed with ash and pyroclastic rocks, Lassen is pretty much all one giant dome of dacite lava. It's about 27,000 years old and rises on the north rim of an ancient caldera formed when a much larger and older volcano erupted and then collapsed. This ancient volcano is usually called Mount Tehama. Two other nearby peaks, Brokeoff Mountain and Mount Conard, mark Tehama's southwest and southeast flanks. Around and below these mountains, still older volcanic rocks indicate that other volcanoes were here even before Tehama. The oldest rocks in the Park date back some 2.5 million years.

One of the Sulphur Works gas vents. Below and to the left of the steam cloud you can see rocks stained yellow by sulfur deposits.

I entered the Park at the southern entrance, a few miles east of Mineral, CA. There I stopped at the south-end ranger station to get some information. I also saw the first of what I hoped would be many new birds for my life-list: a couple of Steller's Jays hanging around the small picnic ground. My first stop within the Park was "Sulphur Works," an array of vents which release a steady stream of sulfide-laden steam into the air. Geologists think that Sulphur Works corresponds fairly closely to the location of the main vent for the long-vanished Mount Tehama.

Being close enough to get these pictures also meant I was more than close enough to smell the venting gas. As a result, I decided that the description of volcanic gas as smelling like rotten eggs is badly mistaken. According to the Park guidebook, the steam contains both hydrogen sulfide and sulfur dioxide, which makes it smell like a mix of rotten eggs and burning matches. I think there was other stuff in there too; whatever it was, the Sulphur Works steam stinks like nothing else I've ever smelled. Even a single whiff is quite un-aesthetic; breathing it for any length of time would probably do evil things to your lungs.

My next stop was at the trailhead to "Bumpass Hell Trail" -- honest, that's its name, right there in the official Park literature! From the trailhead, the trail winds about a mile and a half each way through rocks and trees along a slope on the outer side of the ancient Tehama caldera. The altitude makes walking a bit more tiring than at sea-level, but the scenery makes the walk more than worth the effort. To one side you get good views of Lassen Peak and other large lava formations.

This closer view of Lassen Peak clearly shows the prominent rock formation called Vulcan's Eye.

In the other direction, you get to see sweeping vistas of valleys and mountains, which show why the Cascades are considered some of the grandest scenery in the continental United States.

Vista seen from Bumpass Hell Trail looking roughly southeast, away from Lassen Peak.

Late afternoon is a poor time for birdwatching, but I did see a few birds in the trees along Bumpass Hell Trail: several Steller's jays and a couple of chickadees, which had to be Mountain Chickadees since that's the only chickadee you find at these altitudes.

The trail ends, naturally, at Bumpass Hell, a small valley which contains a large assemblage of fumaroles, mudpots, hot-water springs, and steam vents. Bumpass Hell is actually the vent area of yet another volcano: the ancient (240,000-year-old) dacite dome volcano called Bumpass Mountain. Bumpass Hell is the largest assemblage of volcanic springs west of Yellowstone National Park. It's named after a mountain man, Kendall Vanhook Bumpass. He was first to see the valley, and also its first victim: he lost his leg to severe burns after he stepped in a thermal pool.

"Bumpass Hell." The ponds are geothermally heated mineral-water pools, while the white is mostly deposits of various minerals. Venting steam and gas occur in several places in the valley, testament to the heat that still lurks below.

If you want, you can descend into the valley and walk on the wooden boardwalk which lets one get quite close to the pools and vents. However, it's NOT safe to get off the boardwalk, because the ground is not stable. What looks like firm ground may be no more than a crust covering superheated mud. Large glaring warning signs say that a number of people have been seriously burned because they stepped onto a crust and broke through. A handful have been burned so badly they died of it. The hot mud has been measured at temperatures as high as 240° F: well above boiling at sea level, much less the 7,000-foot altitude of Bumpass Hell.

Along Bumpass Hell Trail, one can find a number of overly friendly chipmunks. They've grown used to getting handouts from people, and readily approach anybody walking along the trail. This one practically posed for my camera, only a few feet away.

After Bumpass Hell Trail, I drove the rest of the Park Road and left by the north park entrance. There are plenty of other things to see along the Park Road. This section of road passes through the area that was devastated by the nuee ardente eruption of May 22, 1915. Major highlights along the road include "Hot Rock," a lava boulder that masses an estimated 300 tons. Hot Rock was moved down the north slope of Lassen to its current place by a giant mudflow in 1915.

The giant lava boulder called Hot Rock. Its name comes from the fact that it was still steaming days after the 1915 eruption. This area was part of the eruption's blast zone. The large, adult trees in the background all grew after the eruption.

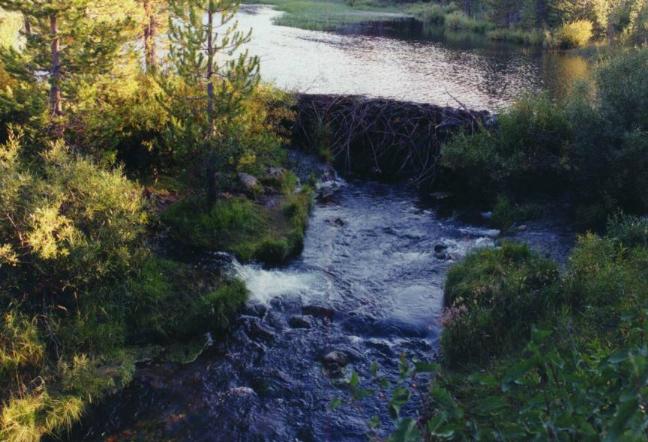

Another stop is in the devastated area from the 1915 eruption. After eighty years, there's surprisingly little direct evidence of the eruption left. Regrowth has filled most of the old blowdown area. A small vale holds Hat Lake, a very photogenic pond formed by a dam. There are also several more chances for superb views of Lassen and its fellow peaks.

Hat Lake, a very nice little pond, with the dam and outflow stream. The ranger told me this was a beaver dam, but a guidebook I bought says it was formed by debris from the 1915 eruption.

Unfortunately, due to very limited time I could only spend half a day in Lassen Park. I would have liked to spend a lot more.

Agenda for day 2: drive north to Klamath Falls, Oregon, via the Klamath Basin wildlife refuges and Lava Beds National Monument.

Further Reading and Links

As a recently-active volcano and a very picturesque area, Lassen Peak and its environs attract a fair amount of attention in books and on the Web. For more information on Lassen Peak and the geology of Lassen National Park, try any of these:

Books:

ROAD GUIDE TO LASSEN VOLCANIC NATIONAL PARK

Decker, Robert & Barbara

c.1997, Double Decker Press

ISBN: 1-888898-02-X

A small booklet that guides you through a tour of the sights visible from the road within Lassen National Park. Easy to follow, easy to understand, and accurate without being too technical. I recommend it highly.

ROADSIDE GEOLOGY OF NORTHERN AND CENTRAL CALIFORNIA

David Alt & Donald Hyndman

c.2000, Mountain Press

ISBN: 0-87842-409-1

This large and well-written book is exactly what the title says: a guide to the geologic sights of Northern California, as seen from various interstates, US routes, and state routes. A nine-page section (pp.269-278) talks about the geology of Lassen National Park.

VOLCANOES IN AMERICA'S NATIONAL PARKS

Decker, Robert & Barbara

c.2001, W. W. Norton

ISBN: 962-217-677-1

This is a guide to the volcanoes found in America's national parks. Pages 76-83 are about the volcanoes of Lassen National Park.

GEOLOGY OF NATIONAL PARKS

Harris, Tuttle, Tuttle

c.1997, Kendall/Hunt

ISBN: 0-7872-1065-X

A textbook on the geology of several major US national parks. Original text written by Ann Harris, updated by Esther Tuttle and Sherwood Tuttle. Chapter 35 is about Lassen National Park.

Websites:

As with all national parks, the National Park Service has a set of pages about Lassen National Park in general. It also has several pages devoted specifically to the Park's geology.

The US National Parks Net is a private organization dedicated to providing thorough and complete information about all US national parks. It includes a section about Lassen National Park.

The United States Geological Survey maintains a page about Lassen Park.

The California Geotour includes a series of links to articles about Lassen Park and vicinity.